WEIGHTS AND MEASURES USED IN PRECIOUS METAL TRANSACTIONS

With regard to precious metal transactions in ancient Egypt, there were different systems available, the one most frequently used being the comparison of the value of a commodity with a certain weight of copper or silver, and very rarely of gold. This weight was called deben (dbn) [Figure 1] and its tenth part was known as kite (kdt) [Figure 2];[27] the latter was apparently not used with copper.[28] The deben was 13 gms during the Old Kingdom, its weight was increased to 91 gms during the Middle Kingdom. In the New Kingdom Period, the deben was divided into 10 kite of 9.1 gms each, with lesser weight expressed as fraction of a kite.[29] Thus it provided a system of 'prices' for use in barter and trade. Weigall has shown evidence of an Old Kingdom writing of the word deben in the context of weights where it was written with a circular determinative.[30] In at least one instance this is more specifically depicted as an open ring.

Figure 1: Hieroglyph writing of "deben" (dbn).[31]

Figure 2: Hieroglyph writing of "kite" (kdt).[32]

Figure 3: Hieroglyph writing of "shaty" (sh‘ty).[33]

The second way of expressing prices is by comparison of the value of a commodity with an object of silver which was variously called shat (sh‘t) / shenat (shn‘t) / shaty (sh‘ty) / seniu (sniw) in ancient Egypt[34] [see Figure 3 for shaty (sh‘ty)]. This unit of value has been the subject of extensive discussion among egyptologists. The most accepted view among egyptologists is that of Peet who translated this word as "piece", although he thought that "ring" was the original meaning.[35] T. G. H. James preferred the even more neutral translation "unit".[36] ern who studied the value of the "piece" (i.e., sh‘ty) was able to prove[37] a previously held view of Gardiner[38] that the sh‘ty weighed 1/12 of a deben.

The relative value of metals were also available in ancient Egypt in terms of deben and sh‘ty. The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus from the time of Hyksos of the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1674 – 1553 BCE) is one such example.[39] The papyrus has 84 problems with worked examples and one particular example deals with the issue of relative values of gold, silver and lead in terms of deben and sh‘ty.

Example of reckoning a bag containing precious metals. If it is said to thee, a bag in which are gold, silver and lead. This bag is bought for 84 sh‘ty; what is assignable to each precious metal?

Now what is given for a deben of gold is 12 sh‘ty, for silver 6 sh‘ty and for a deben of lead 3 sh‘ty. You are to add together that which is given for a deben of each precious metal: result 21. You are to reckon with this 21 to find 84 sh‘ty, for that is what has been bought in this bag. It comes to 4, which you assign to each metal.[40]

The question now arises. Are deben and sh‘ty examples of the "coinage" in ancient Egypt? This we will discuss in the next section.

DEBEN AND SH‘TY (OR SH‘T): EVIDENCE OF "COINAGE" IN ANCIENT EGYPT?

It was stated earlier that coins were unknown in ancient Egypt before the 26th Dynasty. However, there is sufficient evidence to suggest that Egypt had some kind of coinage right down to the Old Kingdom Period (c. 2700 – 2200 BCE). Let us now examine the evidence in chronological order.

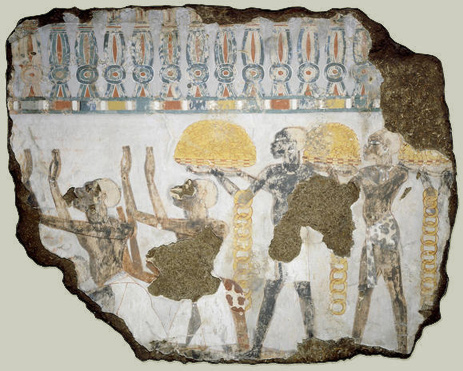

Figure 4: Marketing scene in the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep at Saqqara (5th Dynasty, Old Kingdom Period).[41]

Perhaps the most informative scene concerning sh‘t occurs in a tomb belonging to Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep at Saqqara (Figure 4). Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep were two senior officials who lived in the mid-5th Dynasty of Old Kingdom Period. The scene in their tomb shows a busy open-air market with traders offering a wide variety of goods. There are at least four different vegetable and fruit stalls, two display fish, a woman trader selling vessels and two salesmen standing next to a pitch displaying the cloth. It is the last scene which is of interest to us. Here the two salesmen holding out the cloth, presumably linen make a bargain (row 4, right hand side):

... cubits of cloth in exchange of 6 sh‘t.[42]

The transaction values a particular length of the cloth at 6 sh‘t whereas all other transaction in the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep are straightforward barters. It is interesting to note that the buyer is not shown with any reciprocal object which he can trade against the cloth; but he is given the price of the cloth against sh‘t. The same standard of value also appears in other Old Kingdom texts. The "House-Purchase Document" from Giza uses sh‘t to determine the value of cloth and furniture. Here the house costs 10 sh‘t; in exchange a four-ply cloth is given for 3 sh‘t, a two-ply cloth for 3 sh‘t and a bed for 4 sh‘t.[43]

There is also some evidence of a copper coinage. The Hekanakhte Papyri from the 11th Dynasty[44] of the Middle Kingdom Period (c. 2040 – 1991 BCE) gives evidence of copper deben used for coinage. Hekanakhte, a farmer, sent the letter to his agent saying:

Now see! I have sent you by Sihathor 24 copper debens for the renting of land.[45]

Strangely enough, Baer translated this as "24 deben of copper".[46] James says that the "letter says quite clearly '24 copper debens', not '24 debens of copper', which ought to signify 24 pieces of copper each weighing one deben."[47] It may be emphasized that the reference is made only to the number of debens, clearly suggesting that they were of a standard metal quality as well as of a standard weight.

Papyrus Boulaq 11, first published by A. Mariette,[48] republished by Weill[49] and then Peet,[50] dated to 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom Period (c. 1570 – 1293 BCE), is even more interesting. The majority of the transactions in this papyrus appear to be debits entered against the names of various traders, but there is one transaction that clearly shows a trader paying for his purchase with gold sh‘t.

6. Second month of Inundation, day 25, received from the trader Baki

7. gold 2½ sh‘t in payment for meat.[51]

Interestingly, this is the only known instance where a gold sh‘t was used instead of the usual silver. Acknowledging that this transaction involves payment in gold, James had argued from silence of the entries where commodities are valued in terms of their equivalent in metal that "we should not conclude that the payments were actually made in metal as specified. If they were so made, it would suggest that metals, in particular gold and silver, were commonly used as currency' in the truest sense; from which it should follow that substantial quantities of these metals were in circulation, available for trading, and regularly passed from hand to hand."[52] In the light of Papyrus Boulaq 11, where a trader specifically pays in gold and where commodities are valued in terms of sh‘t of gold, there is no reason to exclude the use of gold in commercial exchanges. It is likely that this trade happened in the upper levels of the ancient Egyptian society. We have already seen the famous Abydos inscription refers to traders dealing in gold, silver and copper.

The early 18th Dynasty stela of Ahmose-Nefertari from Karnak mentions the transfer of 1010 sh‘t in the form of gold, silver, copper, grain and land.

List therefore

Gold: 160, silver: 250, copper: ....

Total: 1010 sh‘t

I have given to her a male and female servant, x amount of grain, 5 arouras of land in Lower Egypt as the 1010 sh‘t though her office was (only) 600 sh‘t.[53]

The Rekhmire's inscription from the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom Period is also worth mentioning. An examination of the tax record on this inscription shows that while the amount of gold paid as tax on offices range from about 5 to 6 deben, the commandant of the fortress of Elephantine pays no less than 40 deben and the commandant of the fortress of Bigeh paid 20 deben. On the other hand, the mayor of Edfu paid 8 deben of gold as tax.[54] It appears that the officials from southern frontier were in a good position to obtain gold.

Papyrus Turin 1881 from the New Kingdom Period is an interesting case. It concerns gold, silver and copper provided by a temple for the rations of the Necropolis. In ancient Egypt it was common for commodities to be valued in terms of metal for barter. In this papyrus, however, the metals are valued in equivalents of khar of grain.

Receipt of the d from the deputy Minkhau of the temple of Isis for the rations of the Necropolis: good gold 1 kite, equivalent to 5 khars (of corn); silver 4 kite, equivalent to 6 khar; a kerchief, equivalent to 2 khar; and 20 deben of copper, equivalent to 5 khar.[55]

The metals along with the garment are classified as d which apart from its primary meaning of "silver", has also acquired the general meaning of "payment" for all sorts of commodities.[56] Commenting on this transaction, Castle says:

In the view of the fact that grain equivalents are given for quantities of metal, it may well be that the metal was provided for the purpose of purchasing the usual grain rations from a third party, more likely a private individual or trader than another temple. On the other hand, the grain equivalents may indicate the usual amount of grain payments which are being supplanted by payments in metal for some reason, perhaps on account of a temporary shortage of grain. In any case, the metal must be seen as a form of currency.

By itself, the fact that d came to acquire the extended meaning of "payment" suggests that the exchange of silver in commercial transactions was or had been a general practice.[57]

Similar conclusions concerning the circulation of precious metals were reached by Kemp. He says that

... we should accept substantial amount of gold and silver was always in circulation. This would explain, for example, the gold found in the First Intermediate Period tombs of the Qau area... It would also explain how gold and silver featured prominently amongst the commodities used by provincial towns and districts for paying local taxes to the vizier's office, as depicted in the tomb of Rekhmira...[58]

If precious metals like gold, silver and copper circulated in ancient Egypt, what was its form? What did they look like?

SHOW ME THE MONEY!

It was mentioned earlier that Weigall has shown evidence of an Old Kingdom writing of the word deben in the context of weights where it was written with a circular determinative and in at least one instance this is more specifically depicted as an open ring.[59] The primary lexical value of deben appears to involve a circular shape, suggesting that originally in the context of metals deben indicated a ring,[60] perhaps of a fixed weight which later became a standard. Weigall's conclusions were rejected by Peet but the evidence is not that easy to dispose off.[61]

In the context of the Hekanakhte Papyri, it was seen that the farmer proposed the payment of land using "24 copper deben". In this case it is clear that the deben is to be understood as a concrete object, not just a unit of weight. The implications of this are enormous. There exists a possibility that this means copper rings weighed a deben each. This is precisely what James had said.

As written this must be translated '24 copper debens', i.e. 24 pieces of copper, each weighing one deben... It may be inferred, therefore, that copper was prepared in small ingots or rings of standard weight for convenience of trade and exchange as early as the XIth Dynasty.[62]

It is interesting to note that the texts that were discussed do not say that either deben or sh‘t were weighed or tested for quality. This suggests that both the buyer and the seller were aware of what a deben or sh‘t meant and what they represented.

Peet also suggested that sh‘t originally referred to a metal object rather than to an abstract measure of value.[63] As mentioned earlier sh‘t appeared to existed alongside with shn‘ / t, in addition to another writing seniu (sniw). shn‘ appears with sh‘t as a synonym in two versions of Spell 129 of the Book of the Dead.[64] In the Hekanakhte Papyri which were discussed earlier, the writing of sh‘t appears to have been emended to shn‘t by the addition of n. This occurs three times in the document. In one case n is written inside the sh of sh‘t.[65]

Wente believes that shn‘ of Spell 129 of the Book of the Dead means "ring" or "seal".[66] Similarly ern has noted that sh‘t "occurs several times in an 18th Dynasty magical text, where it seems to designate the flat "seal" of a signet ring."[67] Thus both deben and sh‘t appear to have a shape of a "ring". Additionally, Castle has pointed out that sh‘t most likely was derived from sh‘, "to cut",[68] and this would refer to its being cut from a parent coil of bar stock.[69]

The evidence from ancient Egypt points to the fact that precious metals were frequently handled in the convenient form of rings. Representations of gold and silver in this form appears in the tombs of Rekhmire[70] and Sobekhotep.[71] The rings often appear to be open and linked in the form of chains [Figure 5(a)]. Actual finds of treasures from Tell el-Amarna also show that silver was also handled in this form [Figure 5(b)].[72]